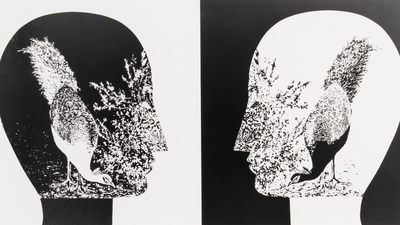

Long before Photoshop, there was Jyoti Bhatt. The year was 1971. India’s premier art institution, the Lalit Kala Akademi, did not yet recognise photography as a fine art category. Artists who worked with the camera were routinely sidelined from its annual exhibitions, their prints placed outside the ranks of painting, sculpture and graphic art. Yet Bhatt — a painter freshly returned to Gujarat after studying graphic printmaking at the Pratt Institute in the US — was determined to break that boundary.Familiar with darkroom techniques such as over-printing, masking using stencils, pushing contrast, cropping and enlarging, he submitted The Face — an image of a human head with a peacock inside it — shot with a camera. “Instead of using the word ‘photography’, I said ‘silver gelatin print’ under medium,” recalls the 92-year-old. “The jury of experts had no idea what silver gelatin print meant and accepted my entry.”Five decades on, this iconic subversion is among a rare group of Bhatt’s experimental black-and-white silver gelatin works now on view in Mumbai. Inaugurated during the ongoing Mumbai Gallery Weekend 2026, A Painter with a Camera: Jyoti Bhatt at Subcontinent Gallery in Fort — on view till February 21, 2026 — foregrounds photography as a central and experimental dimension of Bhatt’s practice. The title pays homage to Painters with a Camera (1968–69), the landmark group exhibition at Jehangir Art Gallery that asserted photography’s credibility when it was still largely excluded from institutional spaces. The works span the 1960s to the 1980s, fractured through mirrors, lenses and multiple exposure, alongside collage and hand-painted images.

Jyoti Bhatt: Jyotsna Bhatt at an Art Museum, Germany, 1978; Silver gelatin print (Copyright of Jyoti Bhatt, Courtesy of Subcontinent, Mumbai)“In many ways, he has pioneered the medium for younger generations of artists in the country. Even in his 90s, he remains deeply engaged,” says Keshav Mahendru, co-founder of Subcontinent.Born in Bhavnagar in 1934, Bhatt — painter, printmaker, photographer and educator at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Maharaja Sayajirao University, Baroda — has been a defining figure in Indian modern art since the 1950s. In 1956 he emerged as part of the Baroda Group of Artists, joined MSU as a lecturer in 1959, and went on to study at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Naples and the Pratt Institute under Fulbright and Rockefeller grants.A restless experimenter, Bhatt’s work moved from Cubism to Pop before arriving at a language shaped by Indian folk and tribal forms. While he worked in watercolours and oils, it was printmaking that brought him wide recognition. By the early 1960s, photography entered his life — initially as documentation of India’s traditional and folk craft practices — before becoming a lifelong artistic pursuit. “My camera recorded the images around me as my eyes saw them. Manipulation of photographic images, inside or outside my darkroom, shaped what was seen into what was felt,” he says.

Jyoti Bhatt: Self-Portrait, Nagda; Silver gelatin print (Copyright of Jyoti Bhatt, Courtesy of Subcontinent, Mumbai)One image on the gallery’s social media shows a young Bhatt in black and white, two glasses — one perched on his forehead — with multiple cameras slung around his neck. “Apart from a bird’s-eye view and a fish-eye view, there’s the photographer’s eye view,” he says. His helper once found a Nikon lens cap left behind by photographer Kishor Parekh. “Now I have the cap. The only missing part is what’s behind the lens,” joked Bhatt to his friend Bhupendra Karia — who soon sent him a Nikon camera from abroad. “Without the cap,” Bhatt laughs, adding that the glasses, exposure meters and the cameras were all borrowed or lent similarly.Bhatt’s work is held in major public collections including the Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; and the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), Bengaluru. “While Bhatt has long been championed for his contributions to ethnographic photography, his experimental photographic practice is yet to receive the sustained critical attention it deserves,” says Dhwani Gudka, co-founder of Subcontinent. “Jyoti Bhatt’s work as an experimental photographer is foundational yet under-exhibited and this is our attempt to help change that.”The selection grew out of “long conversations and time spent closely with the photographs themselves,” Gudka explains. When the gallerists visited Bhatt in Gujarat, they found him a generous host — joking easily, making visitors feel instantly special. “He surrounds himself with art — some his and Jyotsna ben’s, but mostly by friends, mentors and former students,” she says. “We were interested in his image-making process where he treats the image like a surface to think through, revise and transform.” Mahendru points to Baroda (1983): two photographs of MSU students fused through multiple exposure, their faces overlaid with drifting twigs and branches.For younger artists, Bhatt’s practice is a reminder that photography is a medium for thinking, not merely capturing. Gudka highlights a 1977 triad of photographs of Jyotsna Bhatt in Baroda. “An important modern ceramist herself, it shows her as an accomplice of the artist’s experiments with the camera. The care he takes in the darkroom, the patience and rigour, is deeply inspiring.”Some works, Mahendru says, have never been shown before. “They are also rare because they are produced as silver gelatin prints using analogue darkroom processes — exactly how Jyoti Bhatt made them originally. Showing them now allows new audiences to encounter the labour and thinking behind early photography.”At 92, Bhatt remains curious about what digital tools can do. “I return to images made earlier and reuse them in different ways. I am also interested in play — the human mind, chess, board games, arranging and re-arranging letters, numbers and patterns. I think curiosity doesn’t belong to one time,” he says. “The tools may change, but the urge to explore remains the same.”

Leave a Reply